The blog below is an account of my journey to and through the city of Paris in the summer of 2013. I've tried to make it interesting. You can also see the photographs that go with it on flickr.

Don't forget to start at the beginning - Sunday 28th July 2013.

Wednesday 7 August 2013

Monday 5 August 2013

And now the train draws slowly out of Paris Gare du Nord, sliding through anonymous cliffs of office and apartment blocks, out through the banlieu and swiftly into open countryside. I look back to see where we've come from. Planes drift silently in and out of Charles de Gaulle to my left. Soon, we are crossing rivers, passing fields, the villages beyond huddling around their little mock-gothic churches.

This week has been an intense and rewarding experience. It is the longest time I have spent on my own, relying merely on my own resources, for more than a quarter of a century. Paris has changed a bit in thirteen years, but I found that I loved the city even more than I remembered. And I have changed too

On average I walked about five miles a day, a total of about thirty miles in all. I used thirty one metro tickets. I visited twenty churches and seven museums, saw the rooftops of Paris spread before me from four different high vantage points, stopped for eleven espressos or double espressos, drank fifteen beers, ate nine sandwiches, bought nine books and five CDs, sent seven postcards, listened to two whole Wagner operas and three others in part. I set foot in sixteen of the twenty arrondissements. I visited three cemeteries, gave directions to two passers-by, saw one minor road accident, gave money to seven beggars, took 2,351 photographs, wore eight shirts, had sixteen showers, read two books (Requiem for the East by Andrei Makine and Parisians by Graham Robb) and ate eleven peaches.

I spent about 300 euros. I was very frugal. The most striking thing about coming back to France seven years after my last visit, although I did not go to Paris on that occasion, is how fabulously expensive it is now. I do not see how it would be possible for a British family to spend a hotel-based holiday in Paris without spending a fabulous amount of money. But not all Parisians are wealthy, goodness knows. As in London, there has been a marked increase in the number of beggars since my last visit. Many of the street beggars are from ethnic minorities, but in the metro they are almost entirely French, reasonably well dressed and standing with an outstretched hand or cup, perhaps with a sign saying simply 'J'ai faim - merci'.

About half a dozen times during my stay I watched as reasonably well-dressed people, each of them white, got into the metro carriage where I was sitting and, as the doors closed, began in a very loud voice 'ladies and gentlemen, I am very sorry to disturb you, but I have a sad story to tell you...' After recounting their misfortunes, they would walk through the carriage with outstretched hand. I suppose about a third of the people would put a few cents into it.

This week has been an intense and rewarding experience. It is the longest time I have spent on my own, relying merely on my own resources, for more than a quarter of a century. Paris has changed a bit in thirteen years, but I found that I loved the city even more than I remembered. And I have changed too

On average I walked about five miles a day, a total of about thirty miles in all. I used thirty one metro tickets. I visited twenty churches and seven museums, saw the rooftops of Paris spread before me from four different high vantage points, stopped for eleven espressos or double espressos, drank fifteen beers, ate nine sandwiches, bought nine books and five CDs, sent seven postcards, listened to two whole Wagner operas and three others in part. I set foot in sixteen of the twenty arrondissements. I visited three cemeteries, gave directions to two passers-by, saw one minor road accident, gave money to seven beggars, took 2,351 photographs, wore eight shirts, had sixteen showers, read two books (Requiem for the East by Andrei Makine and Parisians by Graham Robb) and ate eleven peaches.

I spent about 300 euros. I was very frugal. The most striking thing about coming back to France seven years after my last visit, although I did not go to Paris on that occasion, is how fabulously expensive it is now. I do not see how it would be possible for a British family to spend a hotel-based holiday in Paris without spending a fabulous amount of money. But not all Parisians are wealthy, goodness knows. As in London, there has been a marked increase in the number of beggars since my last visit. Many of the street beggars are from ethnic minorities, but in the metro they are almost entirely French, reasonably well dressed and standing with an outstretched hand or cup, perhaps with a sign saying simply 'J'ai faim - merci'.

About half a dozen times during my stay I watched as reasonably well-dressed people, each of them white, got into the metro carriage where I was sitting and, as the doors closed, began in a very loud voice 'ladies and gentlemen, I am very sorry to disturb you, but I have a sad story to tell you...' After recounting their misfortunes, they would walk through the carriage with outstretched hand. I suppose about a third of the people would put a few cents into it.

I was impressed by the generosity ordinary people showed to beggars. Several times I saw them bringing bread or coffee to street beggars. In contrast, the headscarved kneelers in metro passages seem to attract very little patronage. With the euro and the pound almost in parity, many items in supermarkets seemed fabulously expensive. How do people survive without an income? Yes, I know what you are going to say. London is expensive too. But the average French wage is half as much again as the average British one. I looked at the prices of flats in the 17e arrondissement, hardly central Paris. There was hardly anything for under half a million euros, and several of the flats in the Villiers area were going for well over a million. It reminded me of coming to France in the 1980s, when we were the poor man of Europe. It is happening again.

One beneficial side effect of my visit to Paris is that I appear to have got my sense of smell back. It happened on Saturday. I was climbing the spiral staircase from the bottom of the catacombs back up to the surface when the rapidly changing air pressure cleared my sinuses. For the first time since an attack of sinusitis back in November, I could smell again. I wandered around Paris in an olfactory daze, smelling bread, fresh fruit, women's perfume, sun tan oil, sweat, flowers, damp, exhaust smoke, cigarette smoke, coffee, stale beer, cologne, old books, grass and the water of the River Seine. This morning as I walked to Gare de Nord from la Chappelle I came down the Rue Fauborg St Denis, the heart of Paris's South Asian area, and the assault of spices, jasmine, incense and fresh fruit from open shop doors was an absolute delight.

M Colignol's shop in Rue des Tres Freres

Five famous but still brilliant things about Paris: the Pompidou centre, the Musee de Cluny, the Eiffel Tower, the catacombs and the metro. Five little-known things I thought were worth recommending to anyone visiting Paris: the church of St-Merri, the concentration camp memorials in Pere Lachaise, M Colignol's shop in Rue des Tres Freres, the Gaudeamus cafe in Rue de la Montagne St-Genevieve just below the steps of St-Etienne du Mont, the bustle of the Jewish quarter in Rue des Rosiers.

And now I am sitting on the 1.30pm East Anglian from Liverpool Street, and it is "nearly done, this frail travelling coincidence", and I look forward to being home.

Sunday 4 August 2013

As with the heart of any great city, central Paris is a quiet place first thing on a Sunday morning. It was about eight o'clock, and the only people around were street sweepers, street sleepers, joggers and dog walkers, as well as the occasional recreational cyclist in full gear heading off for the outskirts and beyond. I wandered up from the Pont Neuf to the Pont Notre Dame, before heading up Rue St Martin. I walked as far as Arts et Metiers, came back, had a double espresso at a cafe looking out across a surreally empty Pompidou Centre square. On my walk I took loads of photographs of odd little details, architectural features, graffiti, stencils, amusing signs. To be honest, it was on my mind that I had not received replies to any of the texts I had sent in the last 24 hours. Either there was something wrong with my phone, or with my family. As it would turn out, it was my phone which was at fault. But it was August the 4th, the day on which I had got married 23 years before on the hottest day of the 20th century, and my mind was elsewhere.

At ten o'clock, I went to mass at St Merri. This is the lovely church beside the Pompidou Centre. It is the chaplaincy for Beaubourg and Les Halles, very much in the liberal catholic movement, with Taize music playing over the PA system, and none of those signs telling you to be silent or not to walk around during services. There is a strong anti-clerical tradition in the French Catholic Church, and you rarely see priests wearing black shirts and dog collars. When I saw the smiling chap in open-necked shirt and chinos setting up the simple altar under the crossing, I guessed that he was the priest. The organ played a setting of the Mass by Alain, no hymns here. The Priest came back and lifted on an alb, put a stole around his shoulders. Still no clerical collar. The altar server didn't even have a robe, just jeans and a t shirt.

It was a lovely, prayerful Mass. There were about sixty of us I suppose, not bad for a parish with hardly any resident population. The main Sunday mass is at eleven-thirty in the Les Halles prayer centre. The ten o'clock crowd were a mixed lot, black and white, elderly ladies, earnest young men, Asian tourists, middle class families with young children, a handful of street sleepers. The priest started by reminding us that we were not here to celebrate our homes, our cars, our families and other possessions. We were to remember that these were transitory things, and all that really mattered was the life of the spirit, and the life of the spirit was Love. The readings were from the book of Ecclesiastes ('Vanity! Vanity! All is vanity!) and St Paul ticking off the Corinthians. Before each reading the priest explained his take on it, and the psalm response was 'from age to age Lord, you have always been our refuge'. The Peace was very enthusiastic, it being assumed that everyone would shake hands with as many of the rest of the congregation as possible. As I say, it was lovely.

It put me right in the mood for my next expedition, which was to head out into the east of Paris to Pere Lachaise cemetery. On the face of it, Pere Lachaise is not as interesting as cimitiere Montparnasse, but I had a number of reasons for coming here, not least because my Paris friends tell me that it is the most beautiful cemetery in the city, and I think they are right. It is true that you cannot be on your own wandering around here like you can at Montparnasse, but it is four times as big and its sloping site gives rise to winding little impasses that can be yours alone for the time you are in them.

If you are planning a visit yourself, it is worth noting that the best thing to do is to take the metro to Gambetta rather than to Pere Lachaise. This brings you in at the top of the cemetery rather than the bottom. This is the quieter part of the cemetery, and very quickly I picked off Maria Callas, Stephane Grappelli and Gertrude Stein without being bothered too much by other visitors.

At this top end of the cemetery the visitor-magnet is the grave of Oscar Wilde. This is a fabulous sculpture by Jacob Epstein. The Irish government, which owns the grave and is responsible for maintaining it, has recently put a Perspex screen around it to stop visitors kissing it with lipstick kisses. Quite how anyone could think Wilde would want to be kissed by a girl is beyond me, though i suppose that they weren't all girls. Wilde's grave is easily found, being on a main avenue, but not all such significant figures are as accessible. I eventually found the tomb of Sarah Bernhardt after much searching, some distance from the nearest avenue. It did not appear to have been visited much at all in recent months.

In one quiet corner of the cemetery is a wall with a memorial to the Paris Commune. The communards had taken advantage of the siege of Paris during the Franco-Prussian War to declare a utopian republic, something along the lines of the one of seventy years earlier, but hopefully without the tens of thousands of opponents being guillotined this time. Incidentally, the French love to discuss and argue about politics so much that there is no chance of the country ever opting for a totalitarian regime. When the revolutionaries of the 1780s and 1790s started executing those who mildly disagreed with them, it was the start of a slippery slope at the bottom of which no one would have been left alive. Anyway, the communards hoped to avoid that. When the siege was over and the mess had been cleared up, they were brought to this wall in their hundreds and shot, their bodies dumped into conveniently adjacent mass graves.

This corner of the cemetery has become a pilgrimage site for Communists, and many of the graves around are for former leaders of the French Communist Party, in its day the largest and most powerful in Western Europe. In the 1980s, when I first started coming to Paris, they ran many of the towns and cities, especially in the industrial north.

Near here are some vast and terrifying memorials to the victims of the German occupation of France and Nazi concentration and death camps. Each camp has its own memorial, usually surmounted by an anguished sculpture, and with an inscription with frighteningly large numbers in it. There is a silence in this part of the cemetery. It is interesting to me that memorials in this part of France refer to 'the Nazi occupation and the Vichy government collaborators', while in the southern half of the country, which was under Vichy rule, the memorials usually talk about 'the German barbarity'.

I sat for a while, and then went off looking for more heroes. Proust and Chopin were easily found, Poulenc less so. Wandering around I chanced by accident on the grave of the artist Gericault, which carries bronze relief versions of his 'Raft of the Medusa', starting point of the Musee d'Orsay, as well as other paintings. To be honest, the most interesting memorials are those to ordinary upper middle class Parisians who were raised to grandeur through art in death in a way that they cannot have known in life.

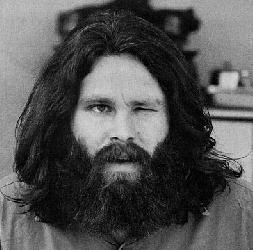

One of the saddest corners, and a rather sordid one, is to the American pop singer Jim Morrison, who died in Paris at the age of 27, burnt out and 20 stone after gorging himself on whisky, burgers and heroin. Well, so did Elvis, you might retort, but at least Elvis had some good tunes. The survival of Morrison's legend seems to rest entirely on the romance of his death and burial. Surely no one can be attracted by his music, those interminable organ solos and witless lyrics? His simple memorial (a bust was stolen in the 1980s) is cordoned off by barriers, and is the only one where a cemetery worker is permanently in attendance. I looked around at a crowd of about thirty people, all of whom were younger than me, and none of whom could have been alive when the selfish charlatan drank and drugged himself to death.

James Douglas Morrison aged twenty-seven

Shaking my head in incomprehension, (I didn't really, but I bet some people do) I finished off my visit by finding Colette, and bumping into Rossini on the way. Then I headed back into central Paris. I was bound for St Merri again, for a concert by the Klaviertrio Wurzburg of piano trios by Mozart, Beethoven and Mendelssohn. It was wonderful, the audience arranged in an octagon around the performers, children sitting on the floor at the front, rapturous applause at the end. I was quite overcome. I took one last tour around the church. "Don't worry, I will come back" I whispered, either to the building or to myself, I'm not sure which.

I was still full of emotion from the Mendelssohn trio, and sat down in the square with a steak hache sandwich to recover. Then I walked westwards into the sun along the Rive Droit, past the bridge loaded with padlocks. This seems to have started originally as a way of lovers plighting their troth after spending a holiday together here - while the lock remains, so does their love, I suppose. They would write their initials in nail varnish on the padlock, lock it to the bridge and throw the key in the Seine. I wonder how many of those romances have actually lasted? It might be an awkward thing to explain to any subsequent lovers. I was pleased and impressed to see that some of the locks were combination locks, which seemed far more sensible. Now the tradition has become that anyone can add a lock to show that they will return to Paris, and now there are hundreds of thousands of the things. I dare say the City Mairie will eventually cut them all away in the middle of the night, and good riddance.

I wandered on, past the Louvre, and then across the top of the Tuileries. The heat was intense, and thousands of feet were raising the dust in front of the Louvre pyramid. As everywhere in Paris, there were young North Africans selling bottled water at a euro a bottle. This has been called a scam by some, but to me it seemed eminently sensible. Sure, the lads are making a decent profit, but it is stil cheaper than it would be in any of the shops, and they were providing a necessary service on such a hot day.

For every water seller there was another North African lad selling Eiffel Tower replicas. There must be an insatiable market for these things. One seller had a sign saying '13 pieces 10 euro' - what on earth would anyone do with thirteen of the things? Give them as gifts, I suppose, but at that rate we should all be over-burdened with miniature Eiffel Towers pressed on us by slightly embarrassed relatives. We should begin to dread our family and friends visiting the city. The world would be drowning in them. With this startling prospect vivid in my mind, I wandered on to the Place du Concorde, where I caught the train back to Villiers.

Saturday 3 August 2013

A Parisian friend of mine recently remarked that Parisians are rude, and you just have to get used to it, but honestly that has not been my experience at all. I have found Parisians consistently polite - no, that word is not formal enough. They are courteous. And they appreciate and respond to courtesy in others. I have experienced this, and seen this, again and again, in shops, cafes, museums, on the street, at crossings, and so on. They show deference to the elderly, and indulgence towards children. They smile when dealing with strangers. There is a formality to Parisian life that allows people to rub along together.

In the Monoprix today, I was exchanging pleasantries with the woman on the till when she said something I didn't understand, and I instantly revealed my Englishness. She continued talking to me in English, and I suppose that her English was about as good as my French - Villiers is not a tourist area. She finished by saying "I am so glad you came to my cash so I could practice my English."

Certainly, you often hear the sound of drivers pressing their horns in the centre of Paris. But almost always this is when cars have stopped at lights, and how can you sit in the centre of Paris staring at a traffic light, when there is so much else to look around at - beautiful buildings, beautiful women, the bustle of life. No wonder drivers miss when the light turns green, and have to be reminded by a driver behind them.

I decided that today was a day for going underground, and I set off to Montparnasse to visit the catacombs. These are a vast maze of tunnels under Paris originally used for quarrying the stone out of which the city's main buildings are constructed. In the late 18th Century, the state of the city's churchyards had become so disgusting that the city removed the bones from all of them. They were brought here at night, the carts coming from the centre of the city accompanied by torch-bearing acolytes and priests chanting the requiem Mass. A skull count showed that almost six million corpses were removed in this way. They were buried deep underground, but these people being Parisians the skulls and bones were arranged in a neat and methodical way, a meaningful chaos. Layers of tibia and femurs are crowned by a layer of pelvises and skulls, and so on. Each churchyard was grouped together, and a plaque shows which parish provided the skeletons.

The work was interrupted by the French Revolution,which provided plenty more corpses for when the work was resumed. Altogether about a kilometre and a half of tunnels were filled with the remains of dead Parisians, and you can walk through them on a winding route under the streets around Montparnasse station. In fact, this is just a tiny fraction of the tunnels. The catacombs extend for hundreds of kilometres under the city, many of them rarely explored and difficult of access. Because of this, they are regularly broken into by intrepid adventurers, and many legends have grown up about parts of the network. However, my favourite story is one which is true.

In 2004, a group of police cadets on a training exercise were given the task of tracking an imaginary criminal in a part of the network which was little known. They got into the system through a manhole, and when they were about a hundred feet underground something rather odd happened. They triggered a motion sensor which set off the sound of barking dogs. Thinking that it was part of the exercise, they headed onwards only to come out into a vast cavern which had been fully equipped as a cinema. An anteroom had been equipped and fully stocked as a bar, and there was also a film storage room. When the cadets reported what they had seen, the electricity board were sent in to work out where the invaders were getting their electricity from. Instead, they found the wires all cut, the equipment removed, and a sign saying 'Don't try to follow us. You'll never find us.'

In the Monoprix today, I was exchanging pleasantries with the woman on the till when she said something I didn't understand, and I instantly revealed my Englishness. She continued talking to me in English, and I suppose that her English was about as good as my French - Villiers is not a tourist area. She finished by saying "I am so glad you came to my cash so I could practice my English."

Certainly, you often hear the sound of drivers pressing their horns in the centre of Paris. But almost always this is when cars have stopped at lights, and how can you sit in the centre of Paris staring at a traffic light, when there is so much else to look around at - beautiful buildings, beautiful women, the bustle of life. No wonder drivers miss when the light turns green, and have to be reminded by a driver behind them.

I decided that today was a day for going underground, and I set off to Montparnasse to visit the catacombs. These are a vast maze of tunnels under Paris originally used for quarrying the stone out of which the city's main buildings are constructed. In the late 18th Century, the state of the city's churchyards had become so disgusting that the city removed the bones from all of them. They were brought here at night, the carts coming from the centre of the city accompanied by torch-bearing acolytes and priests chanting the requiem Mass. A skull count showed that almost six million corpses were removed in this way. They were buried deep underground, but these people being Parisians the skulls and bones were arranged in a neat and methodical way, a meaningful chaos. Layers of tibia and femurs are crowned by a layer of pelvises and skulls, and so on. Each churchyard was grouped together, and a plaque shows which parish provided the skeletons.

The work was interrupted by the French Revolution,which provided plenty more corpses for when the work was resumed. Altogether about a kilometre and a half of tunnels were filled with the remains of dead Parisians, and you can walk through them on a winding route under the streets around Montparnasse station. In fact, this is just a tiny fraction of the tunnels. The catacombs extend for hundreds of kilometres under the city, many of them rarely explored and difficult of access. Because of this, they are regularly broken into by intrepid adventurers, and many legends have grown up about parts of the network. However, my favourite story is one which is true.

In 2004, a group of police cadets on a training exercise were given the task of tracking an imaginary criminal in a part of the network which was little known. They got into the system through a manhole, and when they were about a hundred feet underground something rather odd happened. They triggered a motion sensor which set off the sound of barking dogs. Thinking that it was part of the exercise, they headed onwards only to come out into a vast cavern which had been fully equipped as a cinema. An anteroom had been equipped and fully stocked as a bar, and there was also a film storage room. When the cadets reported what they had seen, the electricity board were sent in to work out where the invaders were getting their electricity from. Instead, they found the wires all cut, the equipment removed, and a sign saying 'Don't try to follow us. You'll never find us.'

Perhaps the cineastes had got fed up with waiting to get into the system officially, because this was the only place all week that I encountered a serious queue. Worse, I was just in front of a small group of people who talked constantly in very loud voices. She was an American who obviously lived in Paris, and they appeared to be young relatives who'd come to stay. She was taking them down the catacombs, and the price to be paid for this by the poor kids was to suffer her pretentious nonsense. She went on about spirituality, and homeopathy, and psychoanalysis, and the inner energy, and so on. Fair play to the kids, they responded enthusiastically enough.

And then she got out some of her stream of consciousness poetry, and started reading it in a loud voice. Well, goodness me. I was put in mind of something the graphic artist Alan Moore said when he was in Hollywood helping turn his 'V for Vendetta' into a film, and he was asked at a director's lunch why he lived in Northampton, England. "Because it keeps me grounded", he replied, and I thought that this was exactly right. It was like the opposite of this pompous woman, although to be fair to her I expect that if I went to live in Paris I would also disappear up my own backside.

The catacombs are brilliant, worth every minute of the queuing time, worth every insufferable stream of consciousness adjective. And then I went and did some shopping. I pottered around in the tourist shops of the Latin Quarter, gazing in awe at the kitschy t shirt designs, the snow globes, the Eiffel Tower thermometers, the chef's hats and aprons, the gros bisous scarves, the ugly jewellery and the rest. Passing these and instead buying some things for which my family might reasonably thank me, I crossed back over the river to go church exploring.

There were three churches close together near the Louvre which I very much wanted to visit, and so I set about them. The first was St Germain l'Auxerrois, which sits directly opposite the eastern entrance to the Louvre beside a magnificent bell tower, which though attached is not actually part of the church at all but a part of the mairie of the 1er arrondissement next door. St Germain l'Auxerrois has a beautiful frontage, and you step into a thrilling interior. This church is almost all of the late medieval period, the French opting for 'flamboyante' when we went perpendicular. The late 19th century glass which replaced that destroyed in the revolution is delightful, a touch of Aubrey Beardsley meets Charles Rennie Mackintosh.

Outside, I watched half a dozen teenage Roma girls with mock petitions try to get tourists to sign them. Nobody was fooled, and in the end the girls gave up and went and lay down in the sun. The idea is to get people to sign for what seems a worthy cause, and then the small print is pointed out to them that they must contribute 30 euros to the cause if they have signed the petition. There are also suggestions that the girls crowd round and pickpocket the signer, though this lot didn't really look up to that. I'd seen some of their colleagues trying to work the same trick outside the Pompidou Centre earlier in the week, and no one was fooled there either.

There had been a lot of publicity recently about Paris scams, and given the strength of the Euro there was a real danger that people would be put off coming here. Francois Hollande's socialist government had worked hard to remove the Roma encampments from around the city, and I certainly did not see the most famous Paris scam of all, the lost ring trick, once during my week in the city. The bracelet scammers are still at work on the steps of Sacre Coeur as we shall see in a moment, but they, of course, are not Roma.

I wandered westwards to St Roche. This huge church is late baroque, built in two separate campaigns of the mid-17th and early 18th centuries under two different architects. Soon after it was completed, the Marquis de Sade was married here. A large dome sits above the altar rather than at the crossing, and beyond it are two nested chapels, one seen through the easterly screen of the other, a pleasant conceit. I quite liked the painting and the gilding, though the statuary was a bit much for my liking, and I do like a bit more coloured glass. But the most moving feature is the memorial to France's deportees, those sent to the concentration camps and death camps in 1940-44 by the occupying German forces and the Vichy French collaborators. More than 60,000 French people lost their lives, many of them Jewish, others including resistance fighters, catholic priests, socialists, people with learning disabilities, Freemasons, Jehovah's Witnesses and Roma. The memorial features the names of the camps and the number of French victims in each, and behind each name is a jar of soil from that camp.

Lost in thought, I headed on to Notre Dame des Victoires, taking a mazy detour through Paris's increasingly busy Japanese district. I got to the church to find that vespers was about to begin. I stood in the open doorway and took a long shot of the opulent 19th century interior, hundreds of candles flickering, hundreds of people on their knees.

On my way up the steps I had given a euro to an old Roma lady who was begging there - as in Ireland, as in all civilised countries, begging is legal in church doorways in France. She was here with an old toothless man, who looked as if he was probably North African. She was wrapped up in a long headscarf, her face in shadow. As I stood there looking inside, she came up to me. "Monsieur! Vous etes Catholique?" I told her I was. She pointed in at the statue of Mary at the far end. "La bonne dame - Elle nous protege!" She pointed to my camera, and then touched her heart. "Photographe-moi Monsieur!"

She stood in front of the church railings, theatrically motioning me to wait, and removed her scarf, shaking out her hair. I saw that she was not an old lady, but thirty years old at the most, her hair raven black. Her face was hardened by poverty, but she still carried the bloom of a young woman in her eyes. She adjusted her scarf, smiled, and I photographed her.

She was excited by looking at her face on the screen, and asked me to give the photograph to her. I explained in my best French that this was not possible, but she laughed and waved her hand. "Envoyez la photo a l'eglise! La prete, il me donne la photo!"

Roma lady outside of Notre Dame des Victoires

She was excited by looking at her face on the screen, and asked me to give the photograph to her. I explained in my best French that this was not possible, but she laughed and waved her hand. "Envoyez la photo a l'eglise! La prete, il me donne la photo!"

I agreed, and wandered on. I don't really know why she wanted me to photograph her. She certainly wasn't a pickpocket, and she didn't ask me for money beyond what I had already given her, which wasn't much. I like to think she wanted to be photographed so that she could look at it and remind herself that she was, in fact, beautiful.

In the evening I wandered back up into Montmartre, hot on the Amélie trail again. Just north of Abbesses metro station is la Rue des Trois Freres, and here is the premises of Monsieur Collignon who owns the fruit and vegetable business. The shop still looks exactly like it does in the film, because the owner has kept the trimmings applied to the shop for the film, including the 'Collignon pere et fils' sign. As well as fruit and vegetables, the outside display includes some garden gnomes and a discreet bin of Amélie posters. Beside the shop is the doorway to the apartment block where Monsieur Collignon lives. Here, Amélie replaces his personal belongings with smaller sizes to punish him for his treatment of his learning disabled assistant. The film used this actual apartment block for those scenes.

Not far off is the small arts cinema where Le Fabuleux Destin d'Amélie Poulain had its premiere before an invited audience of local shopkeepers and residents. This is the cinema where Amélie turns around to watch the reactions of the other viewers at dramatic moments in the films. The wall paintings were the work of Jean Cocteau, and the cinema achieved a certain notoriety in 1930 when there were riots outside in protest at the first showings of Dali and Bunuel's l'Age d'Or.

I climbed up into the heart of tourist Montmartre, which was like Blackpool in high season. I enjoyed it as a spectator, a flâneur, a wanderer. I felt like John Betjeman enjoying watching simple people going about their simple pleasures. The noise, the ice creams, the crepes! I passed le Consulat, the restaurant where Woody Allen dines alone in maudlin fashion in Everyone Says I Love You, and which was reconstructed in precise detail on a Hollywood sound stage for April in Paris. I continued over the hill, past Paris's last vineyard, to au Lapin Agile, a country auberge in its style and setting, but in its time a remarkable cabaret. Both Picasso and Modigliani paid their bar bills here with paintings rather than money.

I wandered back up to the top of la butte. This is by far the most touristy part of Paris, and almost all of the tourists were couples, dewy-eyed and in each others arms, or grumpy husbands and wives reprimanding their children. For a moment, just for a moment, I felt a bit lost for being on my own, for being single, for being a voyeur. And then the moment passed. I turned the corner to glorious Sacre Coeur, the most romantic and photographable church in all Paris. But as I say, I was on my own, and in fact Sacre Coeur is the only church in Paris where photography is not allowed. There were hundreds of people inside, praying, lighting candles, wandering, shouting, taking photographs, being told off for taking photographs. The vast range of 1950s modernist glass is superb, some of the best in the world. I would have loved to have spent an hour or so documenting it. But it was not possible.

I sat for a while, and then wandered back down the hill. Everywhere, signs reminded you to beware of pickpockets, but there were none of the groups of Roma youth of days gone by. What on earth has the Hollande government done with them?

At the bottom of the steps, handsome African men were pulling the bracelet scam. This involves approaching someone, usually a young girl, gesturing for her wrist, and then tying a wool bracelet on to it. The bracelet is not easily removed, and once in place a demand for payment is made, usually about 30 euros but falling swiftly. I saw a group of them pull the trick on two young girls who then laughed and ran off up the steps without paying. For a moment, the group of men looked at each other, as if deciding whether to pursue them. But then they just laughed, and looked around for other victims. As I walked down to the Anvers metro stop, a police car stealthily made its way up to the base of the stairs.

Friday 2 August 2013

The start of Schubert's Winterreise seemed appropriate. After all, I was about to spend a few hours in the company of the dead. But first, a trip to the Rive Gauche. And even before that a double espresso at the cafe on the corner. Just an ordinary street corner cafe, patronised by the blokes setting up the market. Even here a double espresso was more than four euros, a mark of how expensive Paris is becoming for visitors. There are very few English tourists in Paris this summer, and those that are here are mainly middle class families with children, the parents looking slightly stupefied by the amount of money they are spending. But at least we still get 1.10 euros to the pound. Pity the poor Americans, who are doing well to get 0.75 euros to the dollar. "We are spending our children's inheritance, but we feel we have to come to Paris," said one old American boy I spoke to today.

I headed south for St-Germain de Pres. This is often touted as Paris's best church after those on the Île de la Cité, but to be honest I found it disappointing. A Romanesque foundation, certainly, but so restored in the 1880s with murals and frankly bleak glass that it is gloomy and a bit depressing inside. It retains some medieval survivals in the form of glass and sculpture, but it did not lift the heart. It deserves high praise for its historical significance, but not for its sense of the numinous.

Across the road is the Les Deux Magots brasserie. When it was a mere bar, this was where Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir used to hold court. In earlier decades, Ernest Hemingway ran up an unpayable bar tariff here. It is now just another over-priced restaurant. Across the road is Brasserie Lipp, famed for its awful food and obnoxious attitude towards Americans, possibly because Hemingway never paid his bar bill here either.

I headed south for St-Germain de Pres. This is often touted as Paris's best church after those on the Île de la Cité, but to be honest I found it disappointing. A Romanesque foundation, certainly, but so restored in the 1880s with murals and frankly bleak glass that it is gloomy and a bit depressing inside. It retains some medieval survivals in the form of glass and sculpture, but it did not lift the heart. It deserves high praise for its historical significance, but not for its sense of the numinous.

Across the road is the Les Deux Magots brasserie. When it was a mere bar, this was where Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir used to hold court. In earlier decades, Ernest Hemingway ran up an unpayable bar tariff here. It is now just another over-priced restaurant. Across the road is Brasserie Lipp, famed for its awful food and obnoxious attitude towards Americans, possibly because Hemingway never paid his bar bill here either.

I headed south to the Cimitiere Montparnasse. After the Paris churchyards closed in the 18th century, a full three quarters of a century before the English closed their urban churchyards, four great cemeteries were laid out to the north, east, south and west of the city. Pere Lachaise is the most famous, Montmartre the most aesthetically pleasing, but Montparnasse probably the most interesting. I spent about three hours and three hundred photographs pottering about. Some of the famous graves are easy to find because they are well documented, and visitors have placed tributes on them. For example, the first grave I went in search of, Samuel Beckett's, has metro tickets placed on it by visitors as a mark of having waited for something.

I already knew where Beckett's grave was, but two others in the same section were more difficult, as I did not have exact locations. I eventually found the grave of Phillipe Noiret, an actor I very much admired particularly for his role in my favourite film, Cinema Paradiso, but also for his role in Le Cop, which has criminally never had a DVD release with English subtitles. There were no public tributes on it, merely a plaque from his wife saying 'pour mon Cher Philippe' and a picture of a horse. While I was photographing it, four gendarmes, two men and two women, passed behind me and came across to see why I was photographing it. "Noiret!" exclaimed one of the men, and then "mais pourquoi le cheval?" wondered one of the women. But they didn't stop for me to explain, for I had read an article about Noiret about fifteen years previously in a copy of La Nouvelle Observateur while staying in a hotel in Boulogne, and I knew that he had bred horses in his spare time.

The other grave I had hoped to find in this section was that of Susan Sontag, but I couldn't track it down. She only died in 2010, and perhaps doesn't have a headstone yet.

The joint headstone of Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beavoir is easily found by the main entrance, and I thought it rather sweet that they were remembered together. Despite all their efforts for existentialism and feminism, it was like a headstone in a quiet English churchyard which might have 'reunited' or 'together in eternity' inscribed on it. I think he wasn't pleasant company, and while she was certainly more intelligent than he was she made intellectual arrogance respectable. I photographed their headstone more out of interest than admiration.

Philippe Noiret as Alfredo in Cinema Paradiso

The other grave I had hoped to find in this section was that of Susan Sontag, but I couldn't track it down. She only died in 2010, and perhaps doesn't have a headstone yet.

The joint headstone of Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beavoir is easily found by the main entrance, and I thought it rather sweet that they were remembered together. Despite all their efforts for existentialism and feminism, it was like a headstone in a quiet English churchyard which might have 'reunited' or 'together in eternity' inscribed on it. I think he wasn't pleasant company, and while she was certainly more intelligent than he was she made intellectual arrogance respectable. I photographed their headstone more out of interest than admiration.

Admiration was at the heart of my search for a gravestone lost in sections 6 and 7 which I think is not found often. It is for the surrealist photographer Man Ray. I was delighted to find it after barely 20 minutes searching. He designed it himself, and in his own handwriting into the cement it says 'unconcerned, but not indifferent', which could be taken as rebuff to Satre and his circle I suppose. Charmingly, beside it like the other half of a book is a photograph of him with his wife and the inscription 'Juliet Man Ray 1911-1991, together again'. Enough to leave De Beauvoir spluttering into her Pernod.

I headed back into central Paris, and thought I might go to Musee d'Orsay, which I'd last visited 13 years previously. I got off at Sebastapol and first wandered up to Ste-Clotilde. This is another of those cathedral-scale Paris churches. It is big, a 19th century construction in the High Gothic style, all of a piece. I liked it very much. Full of light and enthusiasm, it was very welcoming. Three teenage girls were lighting candles to Ste-Therése de Lisieux, one of them sobbing and the other two comforting her. Then they wandered eastwards, before coming back making lots of noise and leaving the church almost in hysterics, singing and laughing. I liked this very much too. It reminded me of what Pope Francis had recently said: "It is the right of the young to be non-conformist and to challenge our traditions. It is our duty to make the world a safe place for them to do this."

I left the church, and headed down to the riverside and the Musée D'Orsay. This was the first place I'd seen all week where there was a queue. It looked to me as if there was about a 25 minute wait. But what is 25 minutes to wait for the wonders of Van Gogh and Degas, for Monet and Fantin-Latour, in a queue of posh families with bored children called Laurent and Fabia, and tired, fractious English families reining in their children and wondering what they'll tell their bank manager, and vast groups of Japanese teenage girls, and elderly Americans saying "what did they say this place was? A moo-zeum?" And I thought 'fuck this, I'm going up the Eiffel Tower.'

I was immediately refreshed when getting off at Bir-Hakim. This was a cut-price crowd, multi-cultural and classless, out for an afternoon's fun with ice creams, crepes, over-priced cokes and possibly even a model of the Eiffel Tower if they could run to it. The area around the tower was a pleasure garden as it has been for a century and a quarter now. No long queues here. I joined the happy crowds and waited about ten minutes to buy a trip to level two for five Euros. What a bargain! I climbed the stairs up the first three hundred feet or so, silently pleased with myself for passing the out of breath pleasure seekers twenty years younger than me (but how they have enjoyed those ice creams! Those crepes! Those over-priced cokes!) and then paying another six euros to take the lift right to the top. Again, hardly any wait - where are all the tourists? - and then that amazing view that despite the light actually makes photography difficult, you are so high.

And I was on a high, descending with the jolly pleasure seekers. I set out for la Madeleine to see if this vast early 19th century oratory church was as dull as I'd found it previously. And yes, it was. The best thing about it is its severely classical exterior, approvingly nodded off the drawing board by Napoleon himself. It was packed with tourists, and I was tempted to climb to the heights of the vast mock-baroque pulpit and exclaim "listen everyone! Don't you know there's a vast, wonderful church of just thirty years later across the river at St-Clotilde?" But you'll be pleased to learn that I didn't.

Thursday 1 August 2013

The train submerged me beneath polite Villiers to the sound of the Rhine emerging from chaos at the start of Das Rheingold, and then the Rhine Maidens enticed me as fashionable Paris went to work. A Francophile once pointed out to me that most French clothes look as if they'd been bought at C&A ten years ago, and yet the wearers always seem to look so immensely stylish. It must be to do with being French, I suppose. I look French, I've got a swarthy skin, dark hair and a serious expression most of the time. I usually get spoken to in French when I'm in the country, and I'm never bothered by touts or scammers. And yet I always feel scruffy when I'm among French people.

I was bound for St-Eustache, a church I remember loving when I'd last been inside. Back then, there was a tremendous view of it across the gardens of Les Halles, but that is currently impossible while the reconstruction of Les Halles takes place. This was the site of Paris's vast fruit and vegetable market, the equivalent of London's Covent Garden. It was demolished in the 1960s, and straight away everyone knew it was a mistake. Even the signs outside the shopping centre that replaced it admit that the destruction of Les Halles was 'a bruise on the face of historic Paris'. If any good came of it it was that from then on Parisians fought tooth and nail to preserve the historic centre. The Quai D'Orsay railway station was next scheduled for demolition, but it was saved, and today is a fabulous art museum. Now, the ugly underground 1960s shopping centre is being reconstructed, but it won't bring back Les Halles, of course.

St-Eustache was as good as I remembered, another cathedral-scale church of the 16th and 17th centuries, a time at which we had stopped building churches in this country, and would not build the on this scale again for another 200 years. it's flamboyance shows us what English Gothic might have become.

I wandered westwards to the Pompidou Centre. What a dramatic sight this building still is, and I enjoy people calling it the first post-modern building in Europe, because it means that I can correct them. The young Norman Foster beat Richard Rogers by five months, and his curving black glass Willis Faber building can be found not in Paris or London, nor in Berlin, Amsterdam or Barcelona, but in homely Ipswich in Suffolk. I cycle past it most days.

But this is not to cast a shadow on the Pompidou Centre, which has one great advantage over Willis Faber in that it is a public building. As at Musée de Cluny and the arc de Triomphe earlier in the week, I did not have to queue, I just walked straight in. Were they expecting more tourists in Paris this year, and they didn't come?

Up the long ranks of escalators to the top then, the 96 degrees sun burning through the plastic coving, the regular openings filling me with dizzying fear as I looked down in the square below. There were about half a dozen hippies down there making and selling jewellery, seemingly oblivious to the intense heat. They were as brown as berries. I am sure they were there when I last visited in 2000.

The main exhibition was the first major retrospective of Roy Lichtenstein, an artist I have always greatly admired. About 250 works follow him through from the late 1950s to his early death in 1997. Everything is striking, everything makes sense. In his middle years he moved away from pop art to something like abstraction, but you are always conscious that it is not abstraction, rather a facsimile of what abstraction might feel like. Even in his final works, which explore Chinese river themes, he shows that he has no interest in the subject so much as in the way it might be reproduced. A life's work which created a genre.

I wandered pleasantly through the two floors of modern (1900-60) and contemporary (1960-2013) and was amazed to discover that four hours had passed. I could quite happily have spent another four hours in the Pompidou Centre. I think it is one of the best galleries in the world.

Slightly sated by modern and contemporary art, I went into St-Merri, the large medieval church which sits to the south of the Pompidou Centre. This is a fine building, late medieval becoming early modern. There is a vast quantity of late 16th century glass, but some of it is hard to photograph because the easterly side chapels are full of ecclesiastical junk, piled up to keep it out the way. The church is very much in the liberal tradition of Taize, World Youth Day and liberation theology, which I liked very much, and I expect that they are very pleased with the new pope. The church is the chaplaincy for Les Halles and the central streets of the city, and was obviously very energetic in its youth work. It was a shame they were so embarrassed by their old stuff, they didn't need to be. In the south aisle there was an excellent photographic exhibition of portraits of villagers in Guinea-Bissau holding up products they'd either grown, farmed or hunted. The villagers are set back in monochrome, the produce in vibrant colour.

I caught the metro to Cardinal Lesmoines and walked up through the Sorbonne to St-Etienne sur Mont. This was the church I found locked on Tuesday, but coming back I knew it would be open, and it was. The interior is a fabulous confection, the barley sugar spiral staircases lifting to a rood loft which might be a bridge in Venice. This level runs as a conceit around the arcades of the church, creating the effect of a triforium with clerestory above it, filled with vast windows of coloured glass. A wonderful church.

I was bound for St-Eustache, a church I remember loving when I'd last been inside. Back then, there was a tremendous view of it across the gardens of Les Halles, but that is currently impossible while the reconstruction of Les Halles takes place. This was the site of Paris's vast fruit and vegetable market, the equivalent of London's Covent Garden. It was demolished in the 1960s, and straight away everyone knew it was a mistake. Even the signs outside the shopping centre that replaced it admit that the destruction of Les Halles was 'a bruise on the face of historic Paris'. If any good came of it it was that from then on Parisians fought tooth and nail to preserve the historic centre. The Quai D'Orsay railway station was next scheduled for demolition, but it was saved, and today is a fabulous art museum. Now, the ugly underground 1960s shopping centre is being reconstructed, but it won't bring back Les Halles, of course.

St-Eustache was as good as I remembered, another cathedral-scale church of the 16th and 17th centuries, a time at which we had stopped building churches in this country, and would not build the on this scale again for another 200 years. it's flamboyance shows us what English Gothic might have become.

I wandered westwards to the Pompidou Centre. What a dramatic sight this building still is, and I enjoy people calling it the first post-modern building in Europe, because it means that I can correct them. The young Norman Foster beat Richard Rogers by five months, and his curving black glass Willis Faber building can be found not in Paris or London, nor in Berlin, Amsterdam or Barcelona, but in homely Ipswich in Suffolk. I cycle past it most days.

But this is not to cast a shadow on the Pompidou Centre, which has one great advantage over Willis Faber in that it is a public building. As at Musée de Cluny and the arc de Triomphe earlier in the week, I did not have to queue, I just walked straight in. Were they expecting more tourists in Paris this year, and they didn't come?

Up the long ranks of escalators to the top then, the 96 degrees sun burning through the plastic coving, the regular openings filling me with dizzying fear as I looked down in the square below. There were about half a dozen hippies down there making and selling jewellery, seemingly oblivious to the intense heat. They were as brown as berries. I am sure they were there when I last visited in 2000.

The main exhibition was the first major retrospective of Roy Lichtenstein, an artist I have always greatly admired. About 250 works follow him through from the late 1950s to his early death in 1997. Everything is striking, everything makes sense. In his middle years he moved away from pop art to something like abstraction, but you are always conscious that it is not abstraction, rather a facsimile of what abstraction might feel like. Even in his final works, which explore Chinese river themes, he shows that he has no interest in the subject so much as in the way it might be reproduced. A life's work which created a genre.

I wandered pleasantly through the two floors of modern (1900-60) and contemporary (1960-2013) and was amazed to discover that four hours had passed. I could quite happily have spent another four hours in the Pompidou Centre. I think it is one of the best galleries in the world.

Slightly sated by modern and contemporary art, I went into St-Merri, the large medieval church which sits to the south of the Pompidou Centre. This is a fine building, late medieval becoming early modern. There is a vast quantity of late 16th century glass, but some of it is hard to photograph because the easterly side chapels are full of ecclesiastical junk, piled up to keep it out the way. The church is very much in the liberal tradition of Taize, World Youth Day and liberation theology, which I liked very much, and I expect that they are very pleased with the new pope. The church is the chaplaincy for Les Halles and the central streets of the city, and was obviously very energetic in its youth work. It was a shame they were so embarrassed by their old stuff, they didn't need to be. In the south aisle there was an excellent photographic exhibition of portraits of villagers in Guinea-Bissau holding up products they'd either grown, farmed or hunted. The villagers are set back in monochrome, the produce in vibrant colour.

Guinea-Bissau villager with produce

I caught the metro to Cardinal Lesmoines and walked up through the Sorbonne to St-Etienne sur Mont. This was the church I found locked on Tuesday, but coming back I knew it would be open, and it was. The interior is a fabulous confection, the barley sugar spiral staircases lifting to a rood loft which might be a bridge in Venice. This level runs as a conceit around the arcades of the church, creating the effect of a triforium with clerestory above it, filled with vast windows of coloured glass. A wonderful church.

Outside, the steps where Owen Wilson waits in Midnight in Paris were now empty, the wine bottle gone. I resisted sitting down on them (someone might see me) and wandered down Rue de Montagne Sainte-Genevieve, the winding road up which comes the car which will sweep him away to the 1920s. Just below the church was a second hand classical and jazz CD shop, where I sheltered from the sun for a while and bought three CDs for 3 euros each. Wagner's Faust songs (Wagner's music forms the basis for several instances of black humour in Woody Allen's work), Thomas Beveridge's Yizkor Requiem, an interleaving of Jewish and catholic liturgies, and Percy Grainger songs, which seemed oddly parochial in such an exotic spot. A couple of doors down was a cafe with the frontage wide open, a small group of friends drinking pastis and chatting, other people sitting alone and reading over a coffee. Perfect. I sat with a double espresso and carafe of water for half an hour or so, finishing Andre Makine's Requiem for the East and watching groups of serious-looking young people photographing each other on Woody Allen's steps.

I walked on down the hill and took another look inside St Julien le Pauvre, before crossing to the Île de la Cité and walking past the west front of Notre Dame, then east and crossing the bridge to the Île de St Louis, which is home to a wealthy tourist district, all posh clothes shops and expensive restaurants. At the heart is the large, handsome church of St Louis, mostly a 19th century reconstruction but utterly tasteful and seemly inside as befits its district.

The local school sits beside the church, a 19th century building still in use for its original purpose. Outside a sign remembers 'the children of this school taken away during the Nazi occupation because they were born Jewish. They were killed in the death camps. Remember them.'

I crossed back to the Rive Droit and climbed up beyond Rue de Rivoli to the Rue des Rosiers, the heart of the Jewish district. Young Jewish men in dark suits and skull caps bustled about outside a synagogue. A group of them stood with a beat box and video screen outside a kosher butcher's, playing hip hop and showing scenes of the Holy Land. I wasn't sure what they were doing. As I walked past, one of them grabbed my arm. 'Monsieur! Vous etes Juif?' No, I wasn't, I told him politely, so I never found out what it was.

Wednesday 31 July 2013

Without the Metro, Paris could never have become the great city that it is. It sprawls on a bumpy plain at the heart of the northern French bread basket, and of European capital cities only Istanbul, Moscow, London and Berlin are bigger. But it has something that those bigger four do not have. This is a unity. Paris is graspable. It is possible to stand above it, and there are several places to stand, and understand where one thing is in relation to another. They work together to create a greater whole. The metro draws the pieces together. At first the map is a tangle to anyone used to the London Underground map, but the chaos is methodical, which could be said of so much in France.

This morning I travelled on the metro into central Paris, and listened to the overture from Wagner's Tannhauser. On the platform at Villiers the woodwind began the simple sequence which builds, changing key, with a slight sense of uncertainty and then a renewed sense of confidence. The strings bolster the sentiment, and as we headed south east towards the heart of the great city the horn players lifted their instruments to their lips and there began the great cascade.

Tannhauser is one of just two of the major Wagner operas which have an overture, exploring the themes and tunes of the opera to come. The other is Die Meistersinger. The others have what Wagner called a vorspeil, a prelude (in both cases this means literally 'foreplay'), where the music emerges from a primordial silence to begin the story.

As Tannhauser played in my headphones, a man got on the train with a guitar. He was obviously English, and not very much younger than me. He lifted up his guitar and began to strum and croon his take on the Beatles' Yesterday. Now, I wouldn't want to hear it even if the Beatles themselves had stepped into the carriage, so I resorted to the comfort of my headphones. But I watched what happened. It was a crowded train, barely room for him to lift his guitar. But the people around him did not budge. Two old ladies, a young African lad and a businessman stood their ground, but ignored him completely. They did not even look away, which I certainly would have done.

And now, the brass raised itself high into the main theme, the strings cascaded behind as we threaded through the tunnels into central Paris, and I happily admit that tears filled my eyes. What a great country, I thought. If you exclude the Soviet Union, then of the major European states in the 20th century only Poland was dealt a more traumatic hand. Small wonder that France and Poland are the two most nationalistic nations in Europe. We travelled onwards in romantic splendour before I changed at Opera, making my way south for the Sorbonne.

This morning I travelled on the metro into central Paris, and listened to the overture from Wagner's Tannhauser. On the platform at Villiers the woodwind began the simple sequence which builds, changing key, with a slight sense of uncertainty and then a renewed sense of confidence. The strings bolster the sentiment, and as we headed south east towards the heart of the great city the horn players lifted their instruments to their lips and there began the great cascade.

Tannhauser is one of just two of the major Wagner operas which have an overture, exploring the themes and tunes of the opera to come. The other is Die Meistersinger. The others have what Wagner called a vorspeil, a prelude (in both cases this means literally 'foreplay'), where the music emerges from a primordial silence to begin the story.

As Tannhauser played in my headphones, a man got on the train with a guitar. He was obviously English, and not very much younger than me. He lifted up his guitar and began to strum and croon his take on the Beatles' Yesterday. Now, I wouldn't want to hear it even if the Beatles themselves had stepped into the carriage, so I resorted to the comfort of my headphones. But I watched what happened. It was a crowded train, barely room for him to lift his guitar. But the people around him did not budge. Two old ladies, a young African lad and a businessman stood their ground, but ignored him completely. They did not even look away, which I certainly would have done.

And now, the brass raised itself high into the main theme, the strings cascaded behind as we threaded through the tunnels into central Paris, and I happily admit that tears filled my eyes. What a great country, I thought. If you exclude the Soviet Union, then of the major European states in the 20th century only Poland was dealt a more traumatic hand. Small wonder that France and Poland are the two most nationalistic nations in Europe. We travelled onwards in romantic splendour before I changed at Opera, making my way south for the Sorbonne.

On its first performance in the city, the Parisians loathed Tannhauser. It might have been though immoral, but probably it was because of its rejection of Italian opera forms, dispensing with arias and recetatives, and instead growing a long story out of the music.

Emerging above ground, I headed for Musée de Cluny, France's national museum of the Middle Ages. Most of the exhibits are gathered from religious sites in France, but there is also much from Germany, the Low Countries and England. It is hard for me to express how wonderful I think this place is. Three things might help. First of all, the collection of English alabasters of the 14th and 15th centuries. Mostly from altar pieces and depicting incidents in the life of Christ or his mother Mary, the wall of them in the Musée de Cluny is greater in sum than the entire survivals in the churches of the whole of England. Secondly, the intimacy with which you can view stone figures of saints taken from the portals of cathedrals and major churches. And last of all, Cluny possesses the other half of the Thornham Parva retable, probably East Anglia's single greatest art treasure. There are eight saints at Thornham, and the Cluny piece, which would have sat above it, depicts four scenes in the life of the blessed virgin - the Nativity, the Dormition, the Adoration of the Magi and St Anne teaching the virgin to read. The exhibition points out the similarity of the figures with the wall paintings at Brent Eleigh in Suffolk, a slightly unusual thing to read in a French museum.

Afterwards I wandered around, pottering in second hand book and bandes dessinées shops. I went into St-Julien le Pauvre, the oldest church in the city in the shadow of Notre Dame. It's former graveyard is now a little park, and beside it is Shakespeare & Co. and then I caught the metro from St-Martin to Pont Alma, had a look at the graffiti remembering Lady Di and at the pillar her car hit, and wandered down to the Museum of Modern Art. The big exhibition was of the work of Keith Haring, a New York subway artist whose line drawings defined a genre. He died in 1990, but his work is still so immediate, his work having become indistinguishable from that of his admirers. He invented the anonymous line figure shown in different situations, based on the character on warning signs, giving it expression by its apparent movement. Along with Warhol and Lichtenstein, he's one of the most collectible American artists of the last decades of the 20th century.

Keith Haring at the Museum of Modern Art

Later, I caught the metro to just east of Villiers and got off at Blanche on the edge of Montmartre. This is where tourists come to photograph the Moulin Rouge, now a shabby night club, but I was in search of something different. I crossed the road to Rue Lepic. I was on the Amélie trail. About halfway up the road is Les Deux Moulins, the bar in which so much of the action of Le Fabuleux Destin d'Amélie Poulain takes place. It is the same bar that Amélie frequented, with the same name, and they really filmed it inside. I was going to go inside, but the kitchen table charm of the interior in the film is lessened when those tables are filled with teenagers drinking coke, and in any case they ripped out the cigarette counter where the depressive Marianne works to give it more seating space. I thought it might be a good place to come back to in winter. I climbed up the steep road, which is the one where Amélie takes the blind man by the hand and leads him past shops describing what she sees, before depositing him on some metro steps which are actually about a mile away on the other side of Montmartre. The tenement above the steps, incidentally, is where Woody Allen lives in his other hymn to Paris, Everyone Says I Love You.

I wandered up to Sacré-Cœur in the ninety degree heat. The view from the top was stunning, so clear and vivid, the rooftops of the Golden City, the City of Light.

And then all the way down to the bottom, down the steps where Phillipe Noiret finally succumbs to the shoot out in Le Cop, to Abbesses, one of the Art Nouveau metro stations, and where the spiral steps are the deepest in Paris.

Tuesday 30 July 2013

Paris was a city I knew well before I ever visited it. As a child I would study street maps, locate buildings I'd heard of, follow convoluted metro journeys. I did the same for Moscow, New York, even London even though I lived barely fifty miles from it. I did not visit France until I was 25, and not Paris until a few years after that. But it was just as I expected.

Except, of course, for the gaps in between the places I knew so well. That is why the only way to get to know a city is to walk it. I feel that I have spent most of today walking, a day that started at about half past seven with a double espresso at a corner cafe by the Rue des Levis street market. I took the metro from Villiers to the bizarre Arts et Metiers station,which is like a Terry Gilliam interpretation of a Jules Verne submarine. I changed there and got off at Pont Neuf. The light at this point in the day was fabulous, spilling westwards from beyond the Île de la Cité, and I walked into it along the quai of the Seine to Notre Dame.

The square in front was no less busy than it had been twelve hours before, and after fantasising briefly that I was the only one who had left, I stepped inside the cathedral.

I had fond memories of Notre Dame from previous visits, but I had not expected it to be quite so busy. It was shoulder to shoulder at the west end, and the interior of the nave had been sectioned off with ropes in a vain attempt to control the crowds. At first, I took many of them to be Japanese, and could not understand why they were being so badly behaved, blocking the gangways, using flash when the signs said not to, talking when the signs said silence. This seemed most un-Japanese like. And when I got close and could hear their voices I realised that, of course, they were not Japanese at all. They were Chinese, and this was a big difference between the Paris I remembered and the Paris I was seeing now, for thirteen years ago who could have imagined that there would be mass Chinese tourism to Western Europe?

What else has changed in Paris? Among other things, the fast food adverts carry a health warning - 'for a healthy lie you should eat a balanced diet' and 'everyone should eat five portions of fruit and vegetables a day', and so on.

So I shoved my way through the nave as if I was in a dour provincial bus station, and made it into the aisles. Notre Dame is not a huge cathedral, and I decided that I still liked it a lot, despite the crowds. Lots of the visitors were using iPads to record their visits, one girl wandering around with it in front of her face, videoing what she might otherwise have observed. She was experiencing the cathedral through the iPad.

I watched her for a while and then headed down the Île to Ste-Chapelle. Here, the walls of 13th century glass are breathtaking in their intimacy. There is a rolling programme, currently in its fifth year, to restore it bit by bit. So far they've done the south side and the east end, and comparing the restored glass to that still awaiting restoration, the result is stunning.

I pottered across to the Rive Gauche, and became distracted by second hand book shops for a while, before wandering to St-Severin. This church is like a breath of fresh air after the two giants on the Île de la Cité, a fine medieval church with double aisles, and some fabulous glass. The clerestory contains more 14th century glass than there is in the whole of East Anglia, and the east end is filled with excellent glass of 1970 by Jean Bazaine. Best of all, the 19th Century glass all depicts biblical scenes featuring the real life faces of the donors - this works well in, for example, the 'foot of the cross' scene and the 'suffer the children' scene, but is slightly bizarre in 'the beheading of John the Baptist'.

Wandering in this area I found myself increasingly distracted by second hand book and record shops, so it was not for another hour or so that I made it to St-Sulpice. This is a huge late 17th century church as big as a cathedral - imagine St Mary Woolnoth on acid and after a really huge breakfast. And yet, I found I liked it very much indeed, not least because there were lots of people inside, but not tourists. Rather, they were lighting candles, or sitting in thought, or just walking quietly through the vast spaces. And not an iPad in sight.

His name is St Pierre-Julien Eymard, and he founded the order of the Blessed Sacrament. He was made a Saint in the early 1960s. he lies here in a glass casket, like Snow White, albeit more wax than flesh, but still worth seeing.

Except, of course, for the gaps in between the places I knew so well. That is why the only way to get to know a city is to walk it. I feel that I have spent most of today walking, a day that started at about half past seven with a double espresso at a corner cafe by the Rue des Levis street market. I took the metro from Villiers to the bizarre Arts et Metiers station,which is like a Terry Gilliam interpretation of a Jules Verne submarine. I changed there and got off at Pont Neuf. The light at this point in the day was fabulous, spilling westwards from beyond the Île de la Cité, and I walked into it along the quai of the Seine to Notre Dame.

The square in front was no less busy than it had been twelve hours before, and after fantasising briefly that I was the only one who had left, I stepped inside the cathedral.

I had fond memories of Notre Dame from previous visits, but I had not expected it to be quite so busy. It was shoulder to shoulder at the west end, and the interior of the nave had been sectioned off with ropes in a vain attempt to control the crowds. At first, I took many of them to be Japanese, and could not understand why they were being so badly behaved, blocking the gangways, using flash when the signs said not to, talking when the signs said silence. This seemed most un-Japanese like. And when I got close and could hear their voices I realised that, of course, they were not Japanese at all. They were Chinese, and this was a big difference between the Paris I remembered and the Paris I was seeing now, for thirteen years ago who could have imagined that there would be mass Chinese tourism to Western Europe?

What else has changed in Paris? Among other things, the fast food adverts carry a health warning - 'for a healthy lie you should eat a balanced diet' and 'everyone should eat five portions of fruit and vegetables a day', and so on.

So I shoved my way through the nave as if I was in a dour provincial bus station, and made it into the aisles. Notre Dame is not a huge cathedral, and I decided that I still liked it a lot, despite the crowds. Lots of the visitors were using iPads to record their visits, one girl wandering around with it in front of her face, videoing what she might otherwise have observed. She was experiencing the cathedral through the iPad.

I watched her for a while and then headed down the Île to Ste-Chapelle. Here, the walls of 13th century glass are breathtaking in their intimacy. There is a rolling programme, currently in its fifth year, to restore it bit by bit. So far they've done the south side and the east end, and comparing the restored glass to that still awaiting restoration, the result is stunning.

I pottered across to the Rive Gauche, and became distracted by second hand book shops for a while, before wandering to St-Severin. This church is like a breath of fresh air after the two giants on the Île de la Cité, a fine medieval church with double aisles, and some fabulous glass. The clerestory contains more 14th century glass than there is in the whole of East Anglia, and the east end is filled with excellent glass of 1970 by Jean Bazaine. Best of all, the 19th Century glass all depicts biblical scenes featuring the real life faces of the donors - this works well in, for example, the 'foot of the cross' scene and the 'suffer the children' scene, but is slightly bizarre in 'the beheading of John the Baptist'.

Wandering in this area I found myself increasingly distracted by second hand book and record shops, so it was not for another hour or so that I made it to St-Sulpice. This is a huge late 17th century church as big as a cathedral - imagine St Mary Woolnoth on acid and after a really huge breakfast. And yet, I found I liked it very much indeed, not least because there were lots of people inside, but not tourists. Rather, they were lighting candles, or sitting in thought, or just walking quietly through the vast spaces. And not an iPad in sight.

I wandered on past the Jardins du Luxembourg to Rue de L'Odéon. This is a smart street of tall 18th century buildings. Most of them are high end women's fashion shops, but a couple of older book shops survive. It was in this road that Sylvia Beach set up Shakespeare & Co, and a plaque above number 12 remembers the publication of Ulysses.

Above number 4 is a plaque remembering Thomas Paine, 'an Englishman by birth, an American by naturalisation, a Frenchman by decree' who lived here during the revolution and wrote The Rights of Man here. Paine was born in East Anglia, at Thetford in Norfolk, spending his schooldays at Diss in the same county. I remember the poet and Singer Patti Smith saying how proud she was that her ancestors came from Larling at this time, almost exactly halfway between Thomas Paine's two towns. Curiously, there is no plaque at number 16, where Ernest Hemingway lived during his years in Paris.

Ulysses by James Joyce

Above number 4 is a plaque remembering Thomas Paine, 'an Englishman by birth, an American by naturalisation, a Frenchman by decree' who lived here during the revolution and wrote The Rights of Man here. Paine was born in East Anglia, at Thetford in Norfolk, spending his schooldays at Diss in the same county. I remember the poet and Singer Patti Smith saying how proud she was that her ancestors came from Larling at this time, almost exactly halfway between Thomas Paine's two towns. Curiously, there is no plaque at number 16, where Ernest Hemingway lived during his years in Paris.

I was headed towards the Panthéon, but got distracted yet again by an excellent second hand cd shop specialising in classical music and with a large contemporary section. I bought Francis Bayer's instrumental and vocal works and Charlotte Hug's Neuland for solo viola, both for just 3.50 each. I walked past the Panthéon to St-Etienne du Mont, a fine looking church with a minaretesque tower, and three sets of steps, allowing each door to be reached from the sloping street. At the most southerly steps there were groups of young people taking each other's photographs. They were there for the same reason I was - these are the steps where the drunken Owen Wilson waits to get taken back to the 1920s in Woody Allen's Midnight in Paris. There was even an empty bottle of wine to prove that Wilson had been there.